15 May David Tomes, New Urbanism And The Origins Of Norton Commons

Welcome to the Custom Home Builder podcast series, the show for people who enjoy the home design and construction process and who want to listen in as we discuss a variety of topics related to fine craftsmanship, the general home-building process and even interviews with other builders and tradespeople from across our city, the region and even the country as we strive to answer all of your custom and luxury home-building questions and bring you the very best our industry has to offer.

For those of you on Instagram, you can find us at artisansignaturehomes, and that’s where we try to share a new picture from one of our projects almost every day, so check it out.

I’m Greg, your host, and for today’s episode we are joined, as always, by Louisville’s best known and most accomplished custom and luxury home-builder, Jason Black, and we’re also joined by David Tomes…

Jason: Yes, I asked David to join us, he is, I guess, one of the founding developers of Norton Commons and has been very active in the whole new urbanism movement. There’s some exciting news coming to Louisville in 2019, and just invited David to share a little bit about what that means for the city, what it means for Norton Commons. As we get into it, I’m going to introduce David and maybe have him start by giving us a little bit of background on how he got so passionate about this new urbanism movement.

David: My history dates back to Seaside, which I guess was the grandfather of new urbanism, at least what we call the Congress for New Urbanism. Seaside, I made a visit to in the late ’80s. I got it immediately even though there were only a few houses there.

Jason: What drew you there? How did you end up at Seaside?

David: I guess it was one of those change of life things. I was looking to do something new and housing had been suggested to me. I had read in the book American Homes about Seaside, because my real interest at the time was doing really well-detailed smaller homes. I went down and looked and said, “Gee, this is all it was made out to be.” It was great.

Greg: Would you say Seaside’s the best known of these communities?

David: It was the first and I think we all have attachments to Seaside. Anybody that’s been in this movement owes our life work to what was done at Seaside. It really set out to be a very ambitious small town. When you think of small town, it was on 80 acres of beachfront, but it did set out to be a town. It was planned with a gridded street system and a town center. It has become all that and more.

It really led to other followers and I was just in Seaside a couple of weeks back, in fact, for the National Town Builders meeting, and there we studied the successional development after Seaside, the projects that followed in that immediate area and sort of how each learned from the last one. We were at Rosemary Beach, WaterColor and the latest, which is Alys Beach. It’s a great history to follow.

Jason: Was that Andres Duany? Is that who developed most of those?

David: He did three of the four. He did not do WaterColor. I say he, it’s he and his wife. They’re a team, Elizabeth Plater Zyberk, who is also a planner and an architect. They’re both planners and architects. Liz was the Dean of Architecture and Planning down at the University of Miami until recently, so she’s been more in the academic side, but she also worked on many design charrettes.

Jason: It’s safe to say that they’re the godfathers of this whole movement, kind of. They started –

David: I think they were certainly at the forefront of designing Seaside and its successors, and I think they’ve done hundreds of towns and villages throughout the world now, including working with folks like Prince Charles in England and so forth.

Jason: That’s a pretty impressive group.

Greg: In the ’80s when you said you were getting interested in this topic, was this a fairly revolutionary, was this sort of an easy-to-see wave that was coming, or was it just totally out of left field?

David: It’s interesting. I believe it was Time magazine had a picture of early Seaside on the cover and said this was the most important new development in America in 50 years or something. That was one of the other things that got my interest early on. As a result of that whole experience, I began to learn more about it. Actually, Duany at the time used to teach a sort of a three- or four-day course up at Harvard, so I went up for that, and then was totally sold after that experience.

Jason: Drank the Kool-Aid, so to speak?

David: Yeah. His major point that I came away with was that design affects behavior. I’ve learned that as a principle. I was the skeptical developer sitting in the first row of that class and he started the first five minutes saying that, and I thought, “Well, that sounds like some big marketing scheme.” Then over the next half-hour or so, he talked about all the places we pay lots of money to visit and they’re generally these mixed-use type neighborhoods –

Jason: I never thought about it like that.

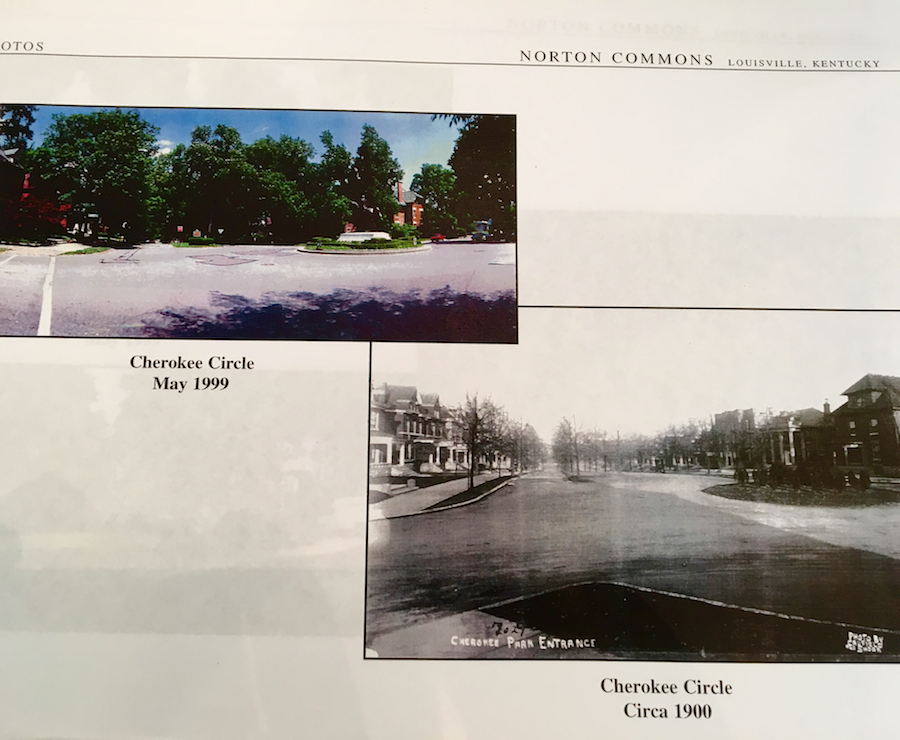

David: Like so many of them we have here in Louisville, the Cherokee Triangle area, The Highlands, Clifton and the like. I got it from that point, and he said all we are is observers of what works, so I began trying to observe, too.

Jason: I’m thinking about some of my favorite cities to visit, and Charleston and Savannah are at the top of the list. They totally hit that movement.

David: Yeah, I think Charleston now has 30 million visitors a year or something like that. That’s unbelievable.

Jason: Wow.

Greg: Yeah, that’s a big number. You could throw a lot of European cities in there, right? Because they’re –

David: Absolutely.

Greg: Small and walkable. The old cities, right?

David: Rome, I’ve made two trips to Italy now over the last few years and I waited much too late in life to do that. I would encourage anybody that’s young like you guys to get over there and –

Jason: I haven’t been called young…

Greg: You are the young guy at the table, aren’t you?

Jason: That’s good, that’s good.

Greg: How did that lead to Norton Commons, and how quickly did it lead to Norton Commons?

David: It’s an interesting thing. After I went to some of those classes, sometimes what you wish for happens. I don’t know how that works out so well, but it seems like –

Greg: You’re a little more open to it, right?

David: I was open to the idea and I said if the right piece of land ever came along that I would like to get involved in something like a new urbanist development project. At the time, again, I began to dabble in housing with Rodney Henderson and Mr. Osborn was involved, too, Charles. We were going through the comprehensive plan effort here in Louisville and, for whatever reason, I guess the Building Association and the environmentalists trusted me enough to present a lot of ideas for the new comprehensive plan.

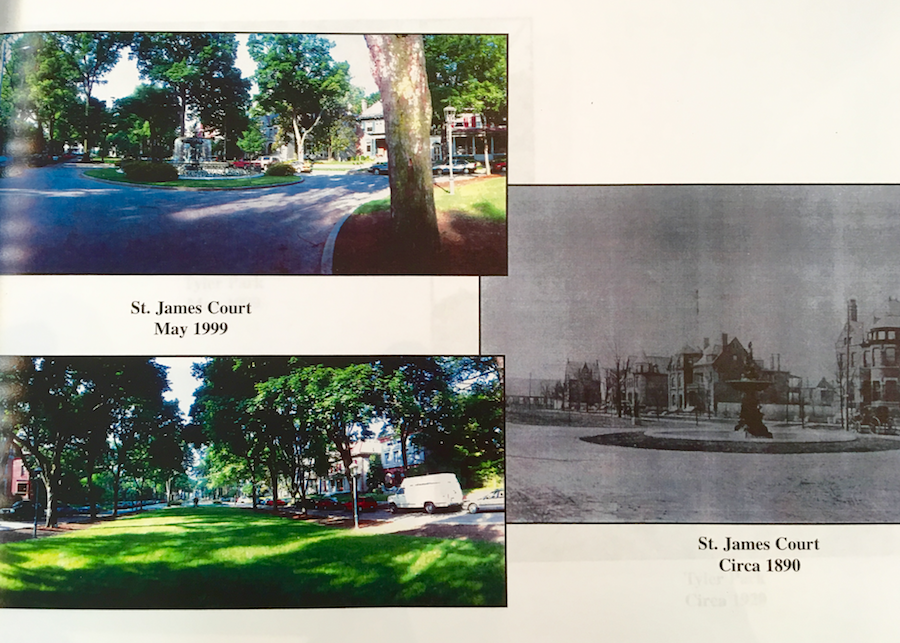

This was the comprehensive plan that was known as Cornerstone 2020, which we developed the idea of Form Districts, which was really more visual in a way, different parts of the city should look and how you mate compatibility within those districts. As a part of that effort, I would show many of these old cities, places like Mariemont up in Cincinnati or Winter Park, Florida or our own neighborhoods of the Park neighborhoods here and talk about those sorts of places, St. James Court, as being beautiful places, quite often lots of density. Everybody got it.

As a result of that effort, in fact, I would use the analogy. I’d say, “You know, we fight tooth and nail to save everything in the Cherokee Triangle with preservation district rules and the like, yet we don’t have rules in place today that would let us build a new Cherokee Triangle without just enormous amounts of waivers and variances and all of that.”

Jason: Yeah, so you could build a suburban sprawl and have these big neighborhoods that just have no –

David: In defense of the building industry, I would say the one thing you were allowed to build was sprawl. Everybody says they don’t like this stuff in many cases but, by the way, it was the one thing you had the right to build. That’s not the industry’s fault, it was the fault of the rules.

As we began to talk about that, we began to allow rules that would allow building new places like Norton Commons and at some point, some of the folks that knew this land had sat here for a while and was going to be developed approached me about trying to put together a team to plan and develop this property. At the time they were talking about a local design team maybe, and I said… This was early in the new urbanism movement and I said –

Greg: Can you give us a year, roughly?

David: This would have been about 1995, and I said, “If you would work with us,” and this was surrounding neighbors and the like, “and ‘work with’ means maybe we don’t agree on everything, but at least we have a dialogue about the important things that should go into a plan.” I said, “I think we would be willing to put together a team that would hire Duany, DPZ and Company, to plan the project.” Everybody thought that was fantastic because they were the leaders in the world in doing these sorts of things.

He was quite expensive to hire and it was quite a risk because we really, at that time, didn’t even have the comp plan done, we didn’t have an enabling ordinance to allow Norton Commons to be built, and we were going to go spend $300,000 plus expenses of other consultants and the like, to hire them to do a plan in a very public process. Every bit of the plan was developed in the public arena.

Greg: This was just out of pocket, right? This is –

David: Oh, yeah, so this was all ante-up money, and if you don’t get the entitlement, you’re pretty sick.

Greg: It’s gone.

Jason: You get a pretty plan.

David: Yeah, but fortunately, we were able to get that done, planned and so forth, and here we are today with Norton Commons.

Jason: Was the difficult part of getting that plan approved is just everything is all purely zoned residential, and that’s what encouraged that suburban sprawl, and more of Norton Commons and these mixed-use developments have commercial and –

David: In Jefferson County, anything that has sewers has a buy right development, underlying development of R4, so…

Jason: That’s strictly residential.

David: Easy to do. You don’t have to go rezone it and so forth, so it’s easy to do and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it was kind of the attitude. We did find, or we felt like there was a great desire, we knew, for the traditional neighborhoods of Louisville, but quite often folks had to put an awful lot of money into an old place in order to live in those neighborhoods. There weren’t always many choices. If you wanted to live in the Cherokee Triangle, you would just possibly take any house you could get that came on the market and then say, “well, hopefully, I get moved in and I’ll find something later that I like better.”

We felt like it was important to offer another suburban park neighborhood. I should say here that we get a lot of arguments sometimes, especially from city people, believe it or not, that, gee, Norton Commons is some sort of a crazy place and these aren’t real people that live there and so forth. I go back and I look at the old photos of Cherokee Triangle and St. James Court and what have you, they look no different than what we look like today. Our trees will grow, our sidewalks will get cracks. This place will patina, too.

The great thing about it is that, what I went back to at Harvard, was we’ve learned that design does affect behavior. The joy I have at 73 years old and getting up to continue to work is that I see how people live and change once they’re living in a neighborhood like this. There really is community. Old people, young people, kids on bikes really have freedom of the neighborhood. That for me is exciting, and just to see that community develop.

Greg: When you talk about behavior changing because of the neighborhood and the community, are you talking about people actually get home from work and they walk around and it’s physical activity, it’s interaction?

Jason: I can attest to this. I’ve built in here for, gosh, probably going on seven, eight, maybe even nine years now, and I never lived here up until the last year. Now that I live here, of course I have my office here, my kids are now going to school in Norton Commons. We go to the doctor in Norton Commons. My wife has her business in Norton Commons.

Greg: Do you leave Norton Commons?

Jason: There’s days that go by that I do not leave the neighborhood, and it’s great. There’s day I don’t get in my car or my truck. Sometimes I’ll take the golf cart or usually, if it’s nice, we’ll just walk. It encourages that behavior and, not only that, you’re talking to your neighbors. There for a while, in the last 10 years, you saw these patio home developments and maybe older people were going in there in these developments of a hundred patio homes that all look the same. It’s just a morbid place to me.

I see a lot of older single ladies and even couples that are retired moving to Norton Commons. They’re always on their porch or they’re talking to their neighbors or in their Bridge club. It really is amazing, the sense of community that Norton Commons has been able to develop.

David: I’ve had folks that could afford to live anyplace in the world that live at Norton Commons and come tell me that they’ve lived in many, many places and this is the best place they’ve ever lived, just because of that community interaction. They’ll say, “I lived in these suburban developments, in my big home and my big yard and never knew my neighbors,” and said, “I moved here and I’ve got 200 friends.” That’s, again, just giving folks natural ways to interact in a community like this. That happens all the time in the city neighborhoods, the older neighborhoods.

We believe that you should have that choice. I started to say earlier, when the Cherokee Triangle was built, when you go back and listen to that history or read that history, it was the same arguments back then. They felt like it was way out in the suburbs and too far out and why are we doing this. It was five miles from the city center at the time, or something like that.

Greg: I think if we can, we’re going to include a photo. I’ll take a picture of the picture you brought in, because it is interesting to look at. What do you say to people now besides, because it’s a different time, right? When Cherokee Triangle was developed, we didn’t have cars. They were waiting for the train line to get developed to make it all the way out to Bardstown Road in Cherokee. What do you say now? The big difference between the other neighborhoods you’ve talked about is the distance from downtown.

David: Yeah, but by relative distances from the center of the city, we’re about 11 miles out as the crow flies, which today is close for any city.

Greg: Fifteen minutes?

David: Yeah, for a neighborhood. We developed, I’ve often, this is New Urbanism 101 stuff, but pre-World War II, the city grew in a very cohesive way. When you really look at everything inside the Watterson Expressway, those were city neighborhoods, they connected. I lived in The Highlands for a while. If I had to go downtown, I had probably thousands of different ways to get downtown without ever really getting on the major arterials. Just that ability to disperse traffic is really important to how you live.

I happen to be a planning commissioner and I know every case. You always can count on two or three things being said, it’s too dense, there’s too much traffic, it’s whatever. The suburbs aren’t dense at all. We’re primarily developing areas that are three units to the acre and under when you really look at it. The suburbs do have traffic issues, though. Why is that? Because every trip, every trip, requires you to get in your car, hit that arterial road because there aren’t connected options like you have in the city.

Greg: Less a question about Norton Commons and more a question about urbanism, when you were talking about the ’50s and the ’60s being developed inside the Watterson, did someone have a plan and say we’re going to do it this way, or is that just the way it sort of grew up?

David: That’s the way it happened. It’s the way it grew up and it was pretty much based on, we were just much smarter with utilities and things like that. You weren’t going to go out and, the water company wasn’t going to expand well beyond its boundaries for nothing. Generally the city grew very cohesively.

Greg: What happened in the ’70s and ’80s that –

David: What happened was post-World War II is really what happened. That’s when the suburban model came along. As I’ve read about it, it seems that we went into World War II basically in a depression. We needed jobs, we needed lots of things. When we came out of World War II, the automobile industry was growing big. It provided jobs. We also had more flexibility to move out. The well-intentioned GI Bill for housing actually only would loan money for new housing and not for refurbishing a house. Consequently, people could find cheap land out in the suburbs and we began to build places that weren’t, they were bedroom communities basically. They didn’t have the other mixed-use aspects to them. It took us 50 years to realize our mistakes, –

Jason: Fifty years to realize …

David: The ills that that was creating. I think part of what is exciting about the Congress for the New Urbanism is it looks for ways to not only rebuild inner city neighborhoods and reinvest, and people like Gill Holland, certainly, at NuLu, now in Portland, have taken on tasks like that. There’s another whole group working in SoBro, Luckett & Farley has been very involved there. There are people that are really working on reinvesting in the cities, same time the new urbanism advocates better suburban green fields and building in the model of towns and villages. That’s a more complicated matter for most suburban developers but, really, there are ways to put together all of the ingredients. The suburbs have got all the ingredients, it’s just specialty developers, quite often, because you’ve got the guy that only builds housing developments, got the guy that only builds shopping centers and you got the guy that only builds apartments or whatever.

What can and has happened in some parts of the country in green field developments, rather than have one person like ourselves who’ve done all of Norton Commons, there have been these groups come together and say, “We’ve developed a town plan. You’re the commercial developer, you do that piece of the plan. We’ll do the housing and so forth and the office buildings,” and it is a cohesive town plan.

The other area that the new urbanists are really working on is the whole idea of how growth works with the environment, so there’s a strong green movement. When you look at a place like Norton Commons, we’re 600 acres, but we’re entitled for about 3,000 dwellings, another half-million square feet of retail and commercial. On one farm, you put all of that density and all of that in place, you probably save six or seven other farms, if you look at good land use and good land stewardship.

Greg: You’re saying that the denser development in Norton Commons is actually more environmentally friendly than the –

David: Yes.

Greg: …suburban sprawl we’ve been doing for years and years. I don’t want to name other subdivisions or anything, but if you drive out of town and it’s house after house after house after house, that’s actually harder on the environment and on infrastructure than at a place like Norton Commons.

David: Yeah, and I’m not trying to criticize or –

Greg: Different strokes for different folks.

David: Or even use in a negative way the idea of sprawl. My definition of sprawl is that it generally is a place that’s a single-use. It’s not that people are building bad houses or any of that sort of thing, it’s just that that’s where it’s at. Actually, when you look at Norton Commons, about 150 acres of the plan are parks, open space and civic spaces.

Yeah, it’s one fourth of the land. Here we’ve gotten the density out of the land and we also have been able to really plan the project to where it protects the watersheds, it does on-site water management in a very beautiful way in parks and so forth, which was the way Olmstead and those guys were doing it a hundred years ago. Again, you learn from the past on many of these things.

Jason: It’s funny how that works. Norton Commons today is, give us a quick overview and then we’ll slide into a little bit more of the CNU. How much developed are we and what do we have left to go?

David: We’re at about 1,400 dwelling units now out of an entitlement of 2,880, so I guess we’re approaching the halfway point. My associate, Charles, and I always say at the end of every year we got 10 more years to go. Some year we’ll be right. We knew going into a project like this that there would be ups and downs in the market, anything this big. Fortunately, we did well during the down time of the market and we’re approaching the halfway point, as I say. We’re moving into what’s now called our North Village which, by the way, we intentionally made all of the housing, all of the buildings in the North Village, including the commercial buildings, will be geothermal heating and cooling. That was a big step towards some environmental things that we felt like were important.

Greg: Was that done at the outset or was that done as you were building in the South Village, you’re still planning the next one?

David: Yeah, we intentionally looked at it and there were a number of reasons that we just said it made sense to go with geothermal. We were disappointed that the government didn’t renew the tax credits for renewables, and that’s something I still hope they’ll do. It makes it much easier to do, but it’s the right thing to do. I have geothermal. I live in the South Village and I have geothermal in my home and I love it.

Jason: For people that maybe don’t understand this whole movement and the planning that it takes and a visionary like yourself, Norton Commons, I think you mentioned, you guys started talking about it in 1995. Here we are, over 20 years later. If my math is right, there was probably over 10 years of planning, because we’ve been building about 11 years or so in here.

David: We went, ’95, I first looked at this land, ’97 we did the design charrette out at Fox Hollow. It was done there, so we’re at the 20th anniversary this year of the design charrette for Norton Commons. We’re excited about that, probably try to do some events this year around that idea. We still were going through the comp plan things once we had it through the design charrettes, so we had to go through an enabling ordinance, which took about 18 months out of my life to get that done. About 2000, we actually went through zoning.

We had some highway issues and surrounding infrastructure that we needed to get improved and we actually worked with the state legislature on some matching funds and local county government to provide the matching funds to get 22 improved. We work with Main Street Realty, who was also developing in that 22 corridor on some of that matching funds. We both needed the roadway improved, so that took some time. 2003, we really got serious, late 2003, broke ground. I think 2004, actually started building houses, had the first move-in in 2005.

While it seems like maybe not a lot of work, it’s a lot of work in 12 years. I sometimes, this is something you learn in Europe, you go there and you think of somebody that worked their whole life on a single building and you say how could they do that? It’s get up one day at a time and just keep going. It’s kind of interesting. I’ve certainly enjoyed it. I hope to live long enough to maybe at least get a spade in the ground on doing another project like this, at least getting one planned and started someplace else.

Jason: It is fun to see, even with Norton Commons as a newer urbanism development, we talk about some of the first streets or couple streets in Norton Commons. You go down today and you’re getting some trees that are 20, 25 feet tall or maybe taller, and it totally changes the feel of the neighborhood once those trees mature. I think that’s what people are sometimes drawn to, these older neighborhoods.

David: There’s all this stuff going on in the city about the heat island and needing more trees and the like. This was a farm and it was primarily treeless. Interesting thing, anyplace we had trees, I can say we saved them. They became the civic park areas and what have you. They formed a nice piece of the park but, in all, without counting private lots, I know in just street trees alone, we’ll plant something like 9,000 street trees in Norton Commons and then that doesn’t include park trees and the likes. We’re doing our part to make it a greener place.

Greg: I know Jason wanted to ask you more about the Urbanism Congress, but before we get there, I’m curious. Looking at Seaside, since it got started and developed long before Norton Commons, what are you looking for? How does Norton Commons end up? What is the end result? You say sold out in 10 years. That means it’s still pretty new, but the south part will be 20-some-odd years old? What is the whole project look like in your mind when you sort of wash your hands and say, “I’m done.”

David: I still think we have 10 to 15 more years. Some of that will be as we get into Oldham County, it’s a little larger lots and a little slower growth there. There’s other growth factors to Oldham County. They only allow you to pull so many permits a year because there are school capacity issues. I think we’ve got that much further to go. We’re pretty excited about the North Village and working very hard to get some synergy around that center. Right now I don’t see that town center having quite as much retail as we do in the south center. We are working on getting some really good density around that town center, so that’s going to help, whatever restaurants and shops we have in that north center.

Greg: I’m curious, and I don’t know how to ask the question properly, but when the project is done, you’ll have homes that are 20 to 30 years older than some other ones. What do you expect the energy to be inside of Norton Commons? Will people feel like the newer section is different entirely? You almost have to look at Seaside or some of these older places to look forward for Norton Commons. Will it be one community and they’re just different aspects or will they feel, do you think, very distinct from each other inside of Norton Commons?

David: I think the hamlet, which is the Oldham County property, will feel distinct because it’s primarily, got a little different character on the streets. It’s meant to be more of a rural hamlet. The tree plantings and things will be done differently than they’re done in the more urban areas of Norton Commons, but I think it will be one community.

Since you mentioned Seaside though, that was part of our progression on my recent trip there. We went from the earliest street, which was very simple cottages, and then when you go to the west side of town, you have much more elaborate homes with towers all over the place and so forth. The towers became one of the symbols of this “this is the new side of town” and people started understanding that the code allowed the towers on the houses and so you began to see more and more of that. That was the way of, I guess, sort of letting the architects and planners show off a little bit, that they tried to think of unique ways to get a beach view.

Jason: How many floors up would I have to go in a tower at Norton Commons to get that beach view?

David: I’m not sure, Jason, but you’ve got a lake view, so you’re –

Jason: Yeah, I think our beach view in Norton Commons is definitely the 150 acres of open and green space that you discussed.

David: We are developing, Jason happens to live on the park right by the amphitheater and a lake. We’re now starting to develop in a serious way that park and the paths through the park and so forth.

Jason: It’s probably one of my favorite parks in Norton Commons because you can walk along the lake. It’s got a good amount of walking path trails, so you can exhaust yourself down there.

David: We find wherever we put in a path, people use it. It’s always interesting. It’s one of the things I learned from Seaside. I used to go back, in the early years where I was just trying to learn, three, four times a year down there just to see what was new. You find that here all the time. People are walking the construction areas just to see the new homes and what they’re like and so forth. These are our residents who have perfectly finished streets, but they choose to –

Jason: I’m always amazed at the residents that they’re stalking my new houses and the new streets, and sometimes they know more about the new streets than I do. I’m like, “But you’re on the South Village.”

David: That’s one of the things we’ve learned here, is that we’ve had many people on multiple homes now, kind of move up, move up or down in the neighborhood. We’ve also had multi-generational families living in the neighborhood but living separately. All of my family lives in the neighborhood. There have been several families I know like that, that Mom or Dad lives a block away and so forth.

Jason: I’m guilty of it. My in-laws live here, aunts, uncles, my wife’s brother, brother-in-law lives here. It wasn’t just because they got a good deal on a house. They like the community, for sure!

That’s a little bit about Norton Commons and maybe we wrap up this episode and we’ll roll into next episode and get a little bit deeper into the CNU and what it means to Louisville.

There you have it, another episode of the Custom Home Builder podcast series with Jason Black and Artisan Signature Homes. For more episodes like this one and to find out more about our company and process, please visit our website at artisansignaturehomes.com.

For all sorts of updates and pictures of our newest projects, you should be following us on Instagram at artisansignaturehomes. Please make sure and introduce yourself and let us know that you’ve been listening to our podcast. If you have an idea for an upcoming episode, let us know. Goodbye for now and we’ll see you on our next episode.